Every month, I interview an author I admire on his literary firsts.

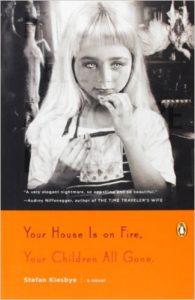

October’s featured author is Stefan Kiesbye, author of Your House Is on Fire, Your Children All Gone (Penguin), a spooky literary novel that made EW’s Must List and was named one of the best books of 2012 by Slate editor Dan Kois.

October’s featured author is Stefan Kiesbye, author of Your House Is on Fire, Your Children All Gone (Penguin), a spooky literary novel that made EW’s Must List and was named one of the best books of 2012 by Slate editor Dan Kois.

Stefan’s also the author of the novella Next Door Lived a Girl (Low Fidelity Press), the LA Noir Fluchtpunkt Los Angeles (Vanishing Point), and the novel The Staked Plains (Saddle Road Press). His latest book, the gothic novel Knives, Forks, Scissors, Flames (Panhandler Books), comes out later this month.

In this interview Stefan offers advice on finding the right indie press for your book, incorporating music into your literary readings, and much more.

Sign up with your email below to be entered to win a copy of Your House Is on Fire — and to get notified of future interviews!

____

Siel: I’ve noticed several of your books are set in quaint small towns — places that appear quiet on the outside, but simmer with violence and mystery under the surface. What draws you to the small town setting?

Stefan: Before I moved to Berlin, I lived in a small town surrounded by small villages. As a teenager I hated that, but looking back it’s fascinating to me how much you knew about your neighbors and the people in town. Secrets were always open. What fascinates me the most is how villagers have to pay for transgressions. Below the surface of modern law, there’s an older set of rules.

Stefan: Before I moved to Berlin, I lived in a small town surrounded by small villages. As a teenager I hated that, but looking back it’s fascinating to me how much you knew about your neighbors and the people in town. Secrets were always open. What fascinates me the most is how villagers have to pay for transgressions. Below the surface of modern law, there’s an older set of rules.

In Knives, Forks, Scissors, Flames, people don’t call the police if you commit a crime. They keep your secrets safe, but they want favors in return. Maybe not right away, but sooner or later you’ll have to forfeit power or influence, or support something you believe is wrong. And events and crimes are never forgotten; the village keeps its narrative intact.

You moved to California not to long ago, to teach at Sonoma State. Has the move affected your writing?

I think all moves do, you just can’t help it. New things come at you and want your attention. You meet people who are specific to a certain place. I’m a big believer in place and that every place creates its own people and challenges and ways of life, and I love looking at new places because they force you to look at life from their angle.

I find your publishing history really interesting! First, a novella with a small press, then Your House Is on Fire with Penguin, then back to small presses for your three latest books. Was the return to small presses a deliberate choice, or was it simply a matter of different books each finding the press that fit them best?

I find your publishing history really interesting! First, a novella with a small press, then Your House Is on Fire with Penguin, then back to small presses for your three latest books. Was the return to small presses a deliberate choice, or was it simply a matter of different books each finding the press that fit them best?

Large presses have more money and more marketing and advertising power, so that’s to your advantage. Small presses operate very differently, and in most cases your involvement with the book itself, from cover art to font to illustrations, is much higher – a great plus. That said, each book seems to take its very own way, and I’m happy to follow. All the different experiences have been wonderful.

What advice do you have for new authors trying to find the right small press for their first book?

That can be a daunting task, but it helps to go to AWP and walk around the exhibition hall and talk to representatives from the presses, to look at their books and authors. Reading the Writers Chronicle and scouring it for contests is a good idea. And friends will always help you, tell you new things you need to know, point you in the right direction. The thing is, there’s no quick solution. In publishing, everything takes a very long time.

I first met you through the Disquiet International Literary Program in Lisbon last year, where you gave a reading accompanied by a soundtrack! Can you share some tips for incorporating music and other sounds into a literary performance?

For me it started with meeting these super-talented musicians in Portales, NM, who were open to spending their evenings rehearsing a certain piece with me. We improvised together, then wrote general directions and themes down. Live music is not always an option (in Lisbon it wasn’t, though I might have been able to convince the violin player who always stood at the corner on the way to that bookstore), but it makes you less lonely on stage, and it gives you more time for small pauses, shifts in the narrative. It also adds a layer of immediate meaning the writing otherwise misses out on. I love when someone just brings a guitar or a mandolin and says, “Okay, let’s try,” and we can improvise the reading that night.

______

Purchase a copy of Your House Is on Fire now, or enter to win one by signing up for the newsletter. Already joined up? Then you’re already entered!

Siel: I read in a

Siel: I read in a

August’s featured author is

August’s featured author is  You’ve said you didn’t expect California to become a bestseller — but that it became one, partly because Stephen Colbert featured your book on his show twice during the whole

You’ve said you didn’t expect California to become a bestseller — but that it became one, partly because Stephen Colbert featured your book on his show twice during the whole

July’s featured author is Kevin Sampsell, author of This Is Between Us, his first novel, as well as the memoir A Common Pornography and the short story collection Creamy Bullets. He’s also the man behind the indie press

July’s featured author is Kevin Sampsell, author of This Is Between Us, his first novel, as well as the memoir A Common Pornography and the short story collection Creamy Bullets. He’s also the man behind the indie press  I think it comes from my early days of writing poetry and then moving on to flash fiction and short stories. I’m a self-taught writer and I think I have a short attention span, so that probably factors in too.

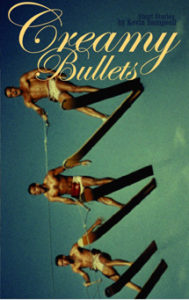

I think it comes from my early days of writing poetry and then moving on to flash fiction and short stories. I’m a self-taught writer and I think I have a short attention span, so that probably factors in too. This is a fun question. For my own books, I actually really like the cover for Creamy Bullets. It just seems very funny and odd and mildly homo-erotic. Those skiing guys flying through the air are a nice image for that goofy book title. My friend, Pete McCracken, designed it.

This is a fun question. For my own books, I actually really like the cover for Creamy Bullets. It just seems very funny and odd and mildly homo-erotic. Those skiing guys flying through the air are a nice image for that goofy book title. My friend, Pete McCracken, designed it. June’s featured author is Victoria Patterson, author of

June’s featured author is Victoria Patterson, author of